Bull trout are perhaps the most misunderstood fish on the west coast of North America. Only recently have biologists been able to accurately distinguish them from their cousins, the Dolly Varden. Their various and often fluid life history forms have also been confounding.

But make no mistake, this Pacific Northwest apex predator is not only a distinct species but one that’s worthy of intense admiration. This apex predator has been eliminated from much of its former range and faces many challenges.

With a better understanding of the life cycle and ecology of bull trout, we can better protect this struggling species.

Overview: What is a Bull Trout?

Bull trout are a char species native to western North America. They are the apex aquatic predator throughout most of their range. Bull trout are an iteroparous salmonid, meaning they can survive spawning. They also have a variety of life history forms, including anadromy.

Extremely cold water and healthy habitats are vital to bull trout survival. Recent years have seen a concerning contraction in their range, especially in the southern end of its distribution and in the upper Columbia basin. Bull trout are currently listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Bull Trout: Taxonomy and Name

The bull trout, known as Salvelinus confluentus, was first described from the Puyallup River in 1858.

It was often classified as a subspecies or variant of the Dolly Varden. A significant taxonomic shift occurred in 1978 when it was reclassified as a distinct species. Despite this, the relationship between bull trout and dolly varden is still widely misunderstood. This is mostly due to the two species’ similar appearance.

Bull trout have a variety of local names like brook char, western brook char, Pacific brook char, red-spotted char, and red-spotted trout. However, few of these names are commonly used and are easily confused with the related brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis).

Evolutionary Origins of Bull Trout

Salvelinus is the genus commonly called char. It traces its evolutionary origins back to the Miocene or late Oligocene period, approximately 5 to 25 million years ago. Salvelinus is closely related to Oncorhynchus, which includes Pacific salmon and trout. They likely diverged around 15 to 25 million years ago.

Salvelinus originates from the North Pacific and Arctic regions. Since then, they’ve undergone significant diversification.

As the Pleistocene epoch and its characteristic glacial cycles commenced, ancestral char populations underwent geographic isolation in various refugia. This period was crucial for the divergence of char species, particularly for the lineage leading to S. confluentus.

Although not entirely clear, Salvelinus curilus (southern/Asian Dolly Varden) may have given rise to several species within the genus, including S. confluentus, S. alpinus (arctic char), S. malma malma (northern Dolly Varden), and S. taranetzi (taranetz char).

The bull trout’s closest relative is Salvelinus malma lordi, the southern/American subspecies of Dolly Varden. The divergence between these two species likely occurred post-Pleistocene. It was driven by isolation in North American refugia, such as the upper reaches of the Columbia River basin. Introgressive hybridization with S. taranetzi in the headwaters of the Columbia and Makenzie Rivers likely occurred during the last glaciation.

While originally evolving in freshwater environments, bull trout developed resident and anadromous forms.

Bull Trout Range

Bull trout are a western North American char and are primarily distributed west of the Continental Divide.

Their historic range in the United States included California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Alaska. In Canada, their distribution spanned British Columbia, the southeastern Yukon system, the Northwest Territory, and Alberta.

Recent years have seen a notable contraction in their range, especially in southern regions. This includes extinction in California, parts of Oregon’s Willamette system, and a presence in Nevada limited to one drainage. Additionally, there have been significant population declines in Washington, Alberta, and British Columbia’s Columbia system and lower Fraser Valley.

Bull Trout: Coloration and Morphology

The color and shape of bull trout varies significantly based on age, sex, and life history.

Bull Trout Color and Morphology

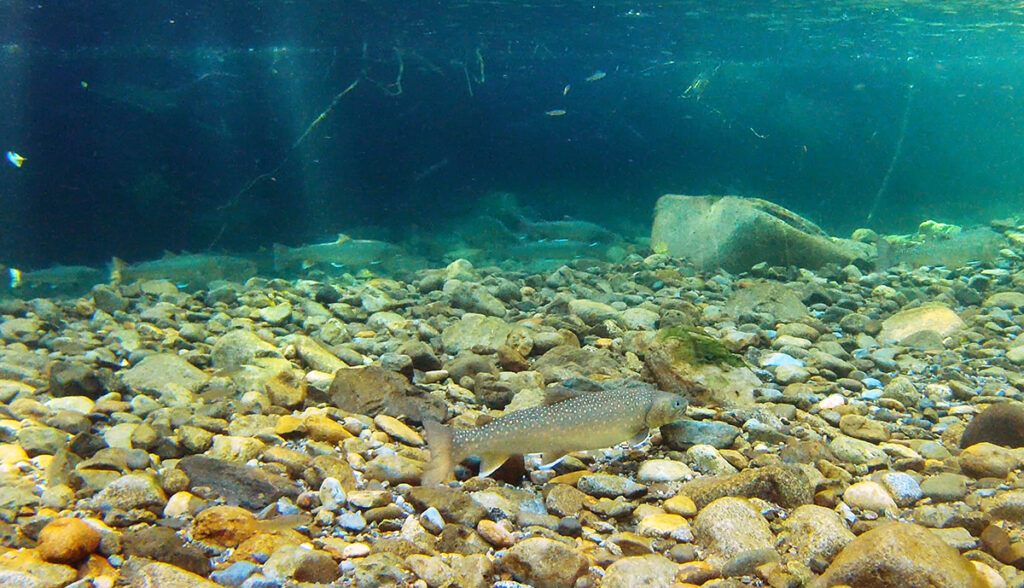

Bull trout have a variable appearance with some general features. Like all char, they have light spots over a dark background. Bull trout have a wide head and large, prominent jaws. A fleshy knob and notch on the nose is another characteristic.

Young bull trout undergo a marked transition in color. Initially, fry are dark-colored. As they mature, their color lightens, revealing characteristic light lateral spots.

Outside the spawning season, juvenile and mature bull trout are generally gray-green, and adorned with small white or pale yellow spots. Some fish also display deep orange to red along the sides. The leading edges of their belly fins (pectoral, pelvic, and anal) are white.

Changes in Appearance During Spawning Phase

Significant color changes occur in bull trout during the spawning season. This change is more intense in males. Their backs turn green, lateral spots brighten to a vivid lavender, and lower sides become orange or coral red. The head, lower jaw, and operculum darken significantly.

Fin colors change, as well. Pelvic and anal fins develop a striking tricolor pattern with white leading edges followed by a black band fading to grey and ending with a brilliant orange trailing edge.

Males are typically slightly larger than females, a trait believed to be advantageous in aggressive encounters among males. Dominant males at spawning sites are often the largest. Some male bull trout develop a hooked lower jaw, known as a kype, which varies across populations.

In areas of sympatry with Dolly Varden, male bull trout may lack a kype or distinctive spawning colors.

Bull Trout vs Dolly Varden: Distinguishing the Two Species

These two species are closely related and often mistaken, even by trained biologists.

Bull trout generally have bigger, flatter, and broader heads than Dolly Varden. They also often have larger upper jaws in proportion to their total body length when compared to Dolly Varden, extending past the eyes. The eyes of bull trout are also positioned more on the top of the head.

Anal fin ray counts are often cited as another distinguishing characteristic, but there is significant overlap between the species.

A better way to distinguish the two fish is through branchiostomal ray counts. Bull trout usually have more than 12 rays, whereas Dollies often fall between 9 and 15. The overlap in ray counts makes this more useful at the extremes.

The only way to truly tell Dolly Varden from bull trout is through DNA testing.

Bull Trout Size and Weight

Bull trout vary significantly in size depending on several factors, including age, subspecies, life history, and available food sources.

Age and Size

Age is the most obvious determiner of size initially. Bull trout fry are tiny and range from about 0.85 to 4 inches (22 to 100mm). Slightly older and larger bull trout parr are still small, averaging around 6 inches (152 mm). Their growth will be slow until they are large enough to switch their diets from invertebrates to small fish.

How large bull trout get is not determined by age. Instead, its habitat and the available food sources that determine their growth potential.

Bull Trout Size by Habitat and Life History

Resident bulls in small streams don’t often get very big. A maximum of 12 inches (305 mm) and 6 ounces (170 g) is common in headwater streams.

Fluvial bull trout, which migrate within rivers, have more feeding opportunities to take advantage of. These fish can grow to 18 inches (457 mm). If quality food sources are available, fluvial bull trout grow much larger.

When available, the ocean also supports rapid and large growth. These anadromous char don’t spend excessive lengths of time at sea but can still find an abundance of nutrient-rich fish to feed on. Anadromous bull trout can exceed 30.5 inches (775 mm) and well over 20 pounds (9 kg).

Bull trout can reach truly large sizes with ample fish as prey. The IGFA world record was caught in 1949 and weighed 32 pounds (14.5 kg). This massive bull was caught in Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho.

Even larger fish have been reported. Bull trout of up to 40 pounds (18 kg) have been reported in Kootenay Lake, BC. These reports are unverified, however.

Most exceedingly large bull trout reside in lakes where they can feed on fish like kokanee salmon.

Bull Trout Habitat

Salvelinus confluentus requires very cold, clean, and oxygen-rich water. Otherwise, this species is adaptable to many habitats like small streams, medium-sized and large rivers, lakes, and the ocean.

Freshwater Habitat

As stated before, bull trout are a fish of cold water. They cannot tolerate temperatures above 60 °F (15.6 °C) and prefer water temps in the 50s.

In the southern part of their range, this need for cold water limits them to higher-elevation streams and watersheds with many cold springs. Riparian shade is also important to keep water temperatures low.

Bull trout will utilize different types of habitat depending on their age. This will be discussed more in the upcoming life cycle section, but to summarize, juvenile bull trout often reside in headwater streams and tributaries of larger rivers and lakes. Fry are strongly bottom-oriented. During the day, they often hide between loose gravel in shallow water.

Once large enough to feed on other fish, bull trout often migrate downstream in search of better feeding opportunities. These larger adult fish reside in bigger rivers and lakes.

Bull trout require quality overwintering habitat, especially in northern latitudes. Resident and anadromous fish seek out bigger water or deep pools with upwellings.

Sea-Run Bull Trout Marine Habitat

Some bull trout also migrate to the ocean, particularly in the Puget Sound. These anadromous fish aren’t known to make lengthy migrations. They also stay close to shore. Bull trout in the ocean make use of mud flats, kelp and eelgrass habitats, rocky beaches, and estuaries.

Spawning Habitat of Bull Trout

Bull trout require cold water for egg incubation. Spawning occurs mostly in small tributary streams. They prefer areas of low gradient, low water velocity, and adjacent to cover.

Spawning sites are usually in areas of gravel aggregation (like tailouts of pools) and groundwater sources in larger streams. And in smaller streams, spawning sites will be suitable pockets of gravel. Gravel size tends to be small at less than an inch (25.4 mm).

The Complex Life Cycle of Bull Trout

The life cycle of bull trout is complex. It’s hard to make generalizations about their habitat and behavior, as individuals and populations may display a variety of habitat preferences and life histories through their life cycles.

Broadly, these life histories include resident, lacustrine, and sea-run populations.

Bull trout are remarkably adaptable fish. They may decide to change their life history form throughout their lives. For example, some may live in tiny headwater streams as resident fish until they mature. Then, they might migrate downstream into a larger river environment in search of better feeding opportunities. They may then decide to spend time in the ocean or residing in a connected lake. Throughout this life journey, these iteroparous fish make repeated spawning journeys to their natal tributary streams, assuming they survive spawning.

Regardless of their particular story, all bull trout start life (and sometimes end it) in tributary stream spawning gravel.

Bull Trout Spawning Season, Behavior, and Conditions

Typical of chars, bull trout are fall spawners. Most spawning occurs in September and October, regardless of latitude. They usually select small tributary streams, though spawning in larger rivers like the Skagit occurs.

Fish usually migrate to their spawning grounds in the summer, where they stage in pools or under the safety of large woody debris or cut banks. Spawning commences once water temperatures drop below around 48 °F (8.9 °C).

Female bull trout construct nests or redds in suitable spawning gravel by turning sideways and beating their tails. Males court females by nudging, quivering, and crossing over the female. Simultaneously, they will fight off other males.

When ready, the female will anchor down over the nest and release a portion of her eggs, which the male will fertilize. Afterward, the female buries the egg pocket and then rejoins the male. There are multiple spawning events over several days.

Like all species of char, bull trout are iteroparous. This means they may survive spawning and can potentially reproduce several times as repeat spawners. After spawning, female bull trout typically leave in search of food, while males may remain at the spawning site longer.

Returning spawners often select the same site year after year.

Development of Eggs and Alevin in Redds

Bull trout embryos require cold, clean, and oxygen-rich water for optimal development. Redds must also be free of fine sediment that could smother the eggs.

The speed at which bull trout eggs develop is temperature-dependent. Warmer conditions will lead to a more rapid progression of hatching as alevin and subsequent emergence as fry. Studies suggest that the optimal development of embryos ranges from 35.6 °F to 39.2 °F (2 °C to 4 °C). But as streams are dynamic environments, actual temperatures vary.

Bull Trout Fry in Streams

Confluentus fry emerge in the spring, typically in April or May. They range from about 0.85 to 1.1 inches (22 to 28 mm) in total length upon emergence.

Newly emerged bull trout are strongly bottom-oriented. Their swim bladders aren’t fully developed, which appears to be an adaptation to keep them from getting swept downstream too soon.

Fry are elusive, often spending daylight hours tucked away between large, loose gravel. They remain in shallow water edges of streams and rivers to avoid predation.

Once their swim bladders fill, bull trout fry still favor stream margins and low water velocities. They may move into side-channel habitats and small pools. Proximity to cover like woody debris, loose rocks, cobble, boulders, and other current breaks seems to be important for these vulnerable, young fish. Fry prefer focal sites, which they return to after feeding. They’ll retain these sites through fall.

Bull trout fry aren’t overtly aggressive. However, they will evict intruders from their focal sites, often by taking up positions about the intruder and drifting back into them. If they must, they may approach intruders head-on. In rarer instances, they may nip the intruder.

Bull Trout Fry Diet and Feeding Behaviour

Fry are opportunistic feeders and eat most organic organisms that fit into their mouths. At first, this is mostly zooplankton. As they get larger, their preferred food sources switch to aquatic insects. This includes mayfly, cassis, and stonefly larvae located on the bottom, plus drifting insects. Terrestrial and aquatic insects near the surface are rarely on the menu yet.

Juvenile Bull Trout – Parr

As young bull trout grow over the spring and summer, their color lightens, and light lateral spots emerge. These parr marks act as camouflage in the stream environment.

Now called parr, these juveniles are slightly less bottom-oriented, though they remain in the lower quarter of the water column. If they were born in larger rivers, juvenile bull trout often migrate to smaller tributaries to rear.

Juvenil bull trout may move to slightly faster water as the summer progresses, but they still prefer pools to riffles and runs. Proximity to cover also remains important. Still relatively unaggressive, they often congregate in pools together when not feeding. Aquatic insects continue to make up the bulk of their diet. Terrestrial insects become an increasing, though minor, portion of their diet as they grow.

Habitat, Diet, and Behavior of Mature Resident Bull Trout in Rivers and Streams

Stream-resident bull trout can be subdivided into two broad categories: those that remain in headwater streams and fluvial.

Fish that remain in tiny headwater streams their entire life cycles tend to be much smaller. Their habitat is often above barriers like waterfalls or velocity barriers. But it’s noteworthy that bull trout are excellent at navigating over barriers, and there is often overlap between non-migratory and migratory forms.

Resident bull trout in small streams often mature after a few years. Most individuals live between four and ten years of age. They continue to feed on aquatic invertebrates their entire lives. The largest and oldest individuals rarely exceed 12 inches (305 mm) in length. These bigger fish may occasionally prey on sculpins and salmonid fry like cutthroat and other bull trout.

Fluvial bull trout occur in larger watersheds. They leave their small tributary rearing grounds as juveniles or adults in search of feeding opportunities downstream. Some individuals migrate 125 miles (200 km) or more. These piscivorous river migrants feed on salmon and trout eggs, fry, and carcasses when available. Juvenile and adult trout, including bull trout, whitefish, and sculpins, are also on the menu.

Mature stream-resident bull trout often use current breaks like boulders, cobble, and large woody debris to ambush their prey. When consuming salmon and trout eggs, they stage behind the spawning fish and pick off loose eggs that drift downstream.

Fluvial bull trout generally mature later and live longer than non-migratory populations in the same region. Ten or 11 years is the typical maximum lifespan, but exceptional fish over 20 years of age have been documented. The oldest recorded bull trout was 24 years old!

Lake-Resident Bull Trout

After rearing in tributary streams for an average of a year or two, some juvenile bull trout migrate into lakes. These fish are variously referred to as adfluvial or lacustrine.

Juvenile bull trout in lakes have a diet similar to stream-resident fish, consisting of aquatic invertebrates like insects, mollusks, Mysis shrimp, and smaller fish. Once they’re big enough, they become highly piscivorous and feed on most fish that fit in their large mouths. Juvenile and adult salmonids like cutthroat and rainbow trout, other bull trout, kokanee, minnows, chubs, suckers, and sculpins are all potential prey where available.

Anadromy: Life Cycle, Habitat, and Diet of Sea-Run Bull Trout

It was only relatively recently that anadromy in bull trout was discovered. This sea-run char was previously mistaken as Dolly Varden. They are most well-known in the Puget Sound of Washington and parts of coastal British Columbia.

Anadromous bull trout start life in tributary streams. After one or more years of residence, they migrate to the Pacific to feed and grow. March through July are the primary months spent at sea. As water temperatures rise, they migrate back into rivers upstream in search of cooler water.

Lengthy migrations are relatively rare, but individual journeys exceeding 155 miles (250 km) have been documented. Most anadromous bull trout instead show high site fidelity. Either way, they typically stay in estuaries and near shore at depths between 3 and 65 feet (1 to 20 m). Proximity to eelgrass seems to be preferred, likely due to having more prey.

At high tide, anadromous bull trout often use intertidal mudflats for foraging. They return to deeper water at low tides.

Sea-going bulls feed on various fish like juvenile salmon and forage fish such as surf smelt, sand lance, and herring.

Bull Trout Predators

Bull trout are apex predators, feeding on other salmonids and species of fish. They have few natural predators besides humans. But as a top predator, they have naturally low abundance. This makes them susceptible to even small changes in their population size.

Eggs, fry, and juveniles are at the highest risk of predation. Birds are a major threat. Dippers, ducks, herons, and osprey are just a few birds that feed on bull trout. Though often small, sculpins can eat relatively large prey. They opportunistically feed on eggs and fry when available. Cutthroat and rainbow trout, invasive brook and lake trout, and adult bull trout are also potential predators.

Salamanders, burbot, and pikeminnows also dine on small bull trout when given the chance. Otters and even garter snakes are also threats. And though also in great decline in much of the bull trout’s range, brown bears are occasional predators of bull trout on their spawning grounds.

Anadromous bulls face a long list of new potential predators in the ocean. Subadult and adult species of salmon, sea-run cutthroat, gulls, cabezon, ling cod, rockfish species, sharks, seals, and sea lions all will eat bull trout smolts and even adults when given the opportunity.

Bull Trout Declines and Threats

There are many reasons for the decline in bull trout populations. Many of these causes overlap with other salmonids like Pacific salmon and steelhead. Others are more particular to bull trout.

Habitat Loss and Destruction

Water withdrawals from streams for agricultural use is a huge problem for bull trout and other salmonids. This results in less available habitat, warmer water temperatures, and reduced population connectivity. If and when this water is returned to the river, its quality is typically severely reduced. Water withdrawals for domestic use also negatively impacts bull trout, though not to the extent of agricultural purposes.

Livestock ranching poses another threat. Reduced streamside vegetation is a consequence of traditional ranching practices and elevates stream temperatures. Furthermore, cattle presence in streams heightens sedimentation, diminishes water quality, and destroys bull trout habitat like undercut banks.

Clear-cut logging mirrors the negative impacts of ranching. It also reduces large woody debris, which bull trout rely on.

Urbanization further escalates the challenges. It significantly lowers water quality, simplifies habitats, raises temperatures, and intensifies peak flows.

The combined effects of habitat loss and alteration form a complex web of challenges for bull trout populations.

Hybridization and Introduced Species

Introduced char species are another significant threat to bull trout. Invasive brook and lake trout have resulted in extirpation in some populations.

Brook trout present a particularly serious challenge through hybridization. Although adult bull trout are more dominant, they mature slower than brook trout. Brook trout reproduce more quickly and at higher volumes. They readily hybridize with bull trout, leading to declines in bull trout populations. These negative effects are exacerbated when large brook trout prey on young bull trout.

Introduced lake trout fill the same ecological niche as bull trout and emerge as fierce competitors. Large lake trout not only prey on smaller bull trout but also compete for the same food sources, such as kokanee. They reduce the amount of food available to bull trout and have caused localized extinctions in some lakes.

Conversely, the closely related Dolly Varden does not pose a significant threat to bull trout. They sometimes hybridize but do not form hybrid swarms. These two species co-evolved, and where their ranges overlap, they generally occupy different ecological roles and habitats.

Overfishing and Population Declines

Despite the absence of commercial fisheries directly targeting bull trout, fishing activities contribute to population declines. In particular, the use of gillnets inadvertently captures bull trout as bycatch. This issue is notably severe in the Olympic Peninsula of Washington, where gillnet fisheries have drastically reduced anadromous bull trout populations. Bycatch of bull trout in the Columbia may have also led to population declines in its tributaries.

Bull trout are also vulnerable to sportfishing pressure due to their ease of capture. This susceptibility has necessitated the prohibition of bull trout fishing in many regions. However, in some areas, such as Washington’s Puget Sound, the retention of bull trout remains permissible despite significant declines statewide!

Historically, bull trout were often dismissed as a “trash fish.” They were frequently harvested under the misidentification of being Dolly Varden, a different char species. Additionally, their predation on young salmon and steelhead led to targeted killings.

The Negative Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change significantly impacts bull trout, primarily due to their reliance on cold water. Natural climate fluctuations have influenced bull trout historically, even contributing to their speciation. This natural variability has caused some natural fragmentation in their distribution.

However, global warming has been accelerated by human activities. These changes manifest in more frequent droughts, less snowpack, increased peak flows, and rising water temperatures.

Bull trout are increasingly confined to cooler, high-elevation habitats. Suitable environments for them are diminishing, causing further fragmentation and simplification in their life histories. This ongoing habitat shrinkage poses severe risks for bull trout populations and escalates the likelihood of localized extinctions.

The interplay between natural climate variation and human-induced warming creates a precarious situation for bull trout.

The Bull Trout: Unheralded King of the Northwest

The story of the bull trout is a reminder of our interconnectedness with nature and the importance of acting as responsible stewards of our planet’s precious resources.

The survival of bull trout hinges on the conservation of cold, clear, and connected waterways. Conservation efforts for this apex predator serve not only to protect this unique species but also to maintain the ecological integrity of entire freshwater ecosystems.

Understanding and mitigating the impacts of human activities, such as overfishing, habitat alteration, and climate change, are crucial. The health of bull trout populations is an indicator of the overall health of aquatic systems. Their protection isn’t just about preserving a single species but about safeguarding a complex and vital ecological web.